Most elements of art exist somewhere in a continuum between order and chaos. Both of these extremes lead to a feeling of meaninglessness in the work. A completely predictable pattern seems mindless and automatic, and complete randomness seems incomprehensible and without information.

Unbroken Patterns<————Varied Patterns———-> No Perceptible Patterns

Robotic/Mindless<———-Art/Expression—————> Random/Noisy

When applied to melodic lines, one factor that gives these lines a desirable level of meaning is convolution or “folded-ness.” Just as in folding paper, where there is a level of variation and pattern that makes an interesting object, there is a level of folding that makes an interesting melody. (or improvised solo) Let’s look at how we can “fold” our lines. In order to isolate this melodic contour, we will use a steady rhythm; how the rhythm varies is an equally important factor we will discuss in a future lesson. We also will not get into tonality: for example, passing tones or modulation; today we are looking at direction only.

Start with a Flat Piece of Paper

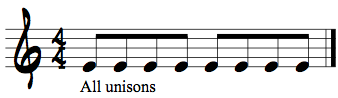

For discussion purposes, we can think of a flat line of the same pitch repeated, like this:

(audio example A below)

Needless to say, this is highly predictable!

Let’s now look at the various direction or contour changes that add interest to our melody.

Folded Contours

Each of these elements contributes to the convolution of the line, with order on left and chaos on the right, and balance in the middle. Keep in mind that if all these factors are “cranked” the melody might be overwhelmingly complex. Sometimes increasing one of these will require the others to be reduced to fit the overall level of intensity required.

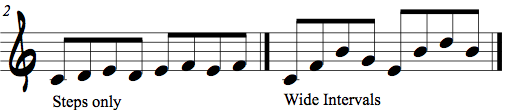

1. Interval motion: this is the size of the intervals (pitch distance) from note to note. This means a scale is less interesting than a line with larger leaps.

Unison—–Stepwise (2nds)—- Skips (3rds)—– Wider Intervals (4ths or more)

(Audio examples B and C below)

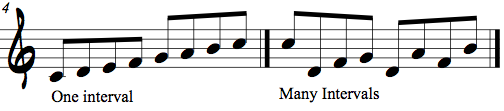

2. Interval variety: a greater number of interval sizes will make the melody more interesting than a line with a single interval. While minor and major versions of the same interval (such as major and minor 2nds) embody some variation, it is less of a difference than between different-sized intervals. (such as 3rds and 5ths)

Single interval—— Several intervals——— All Intervals

(Audio examples D and E below)

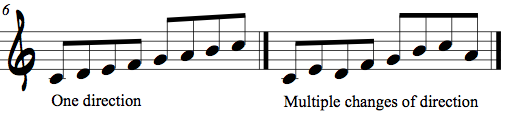

3. Direction change: This is the closest to our “origami” model in that the melody can have a “folded” quality. When the line goes from ascending to descending intervals, the line becomes more interesting. This can be achieved as a transformation of a scale by “swapping” two tones. This adds both a direction change and a new interval.

One direction*——Some direction changes——Many direction changes

(Audio examples F and G below)

*Not the boy-band “One Direction.”

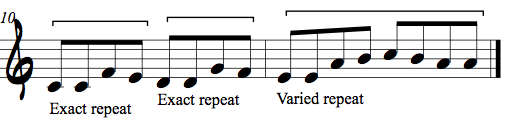

4. Sequence: a recognizable interval pattern that repeats. This is the pitch component of a melodic motif, and can convey intent and intelligence. Once again, excessive sequence repetition creates a mindless “wallpaper” pattern, while no sequential repetition seems aimless and devoid of information. There are several components to sequential patterns: how many repeats, how literal (similar) they are, and how they relate to harmony and rhythm.

More than 3 iterations—— 2-3 iterations——– no repeats

Exact repeats———-Varied repeats——— Complete variation

(Audio example H below)

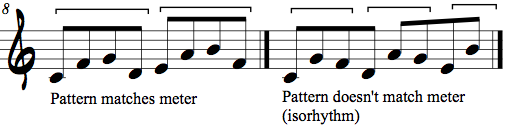

Pattern matches meter—–varied/displaced—— Doesn’t match meter (isomelody)

(Audio examples I and J below)

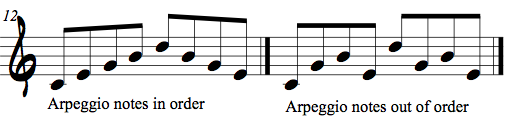

5. Arpeggiation: outlining a chord shape. Generally playing a broken chord carries less intensity than moving in and out of the chord tones; this is a bit more complex, because a chord conveys harmony, and this is a sign of intent, so no implied chord conveys low intensity. However, arpeggiating a chord creates a static harmonic moment, since all the tones are equally resolved with regard to harmony. Another dimension is the order of the notes; playing them in order involves no directional change and fewer intervals.

Arpeggiated chord——-Mixed chord and non-chord

Chord tones in order———Chord tones not in order

(Audio examples K and L below)

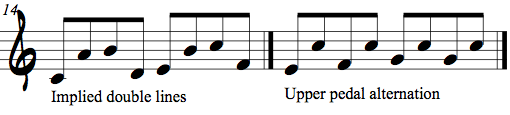

6. Double, broken or self-accompanying lines: Melodies that imply two independent lines create more interest. When one of the implied lines is static or slow, this technique is less intense. When both implied lines move, this is very strong. An “upper pedal” is a common example of static and moving lines together.

Single implied line—- Mixed static and moving—– double moving lines

(Audio examples M and N below)

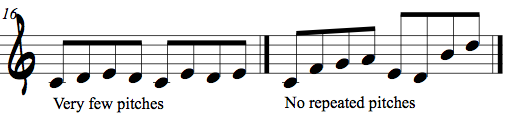

7. Number of pitches: the more unique tones that occur in the line, the more interest. A small number of tones makes a line less interesting.

Small number of tones—–more unique tones——No tone repeats in phrase

(Audio examples O and P below)

Grand Contour

Even when you don’t consider harmonic movement, rhythm, articulation or style, just the interval contour of the melody can make all the difference. Like the origami made from a flat piece of paper, the same raw material can be configured in many ways to create interest and feeling.

Audio Examples: